As BID turns twenty years old, we want you to help us #EndDetention so that we are no longer needed. This summer we have a range of Anti-Birthday gifts ranging from £15 to £250 which can be purchased to support our work. Over the past few weeks, we have been focusing on the many barriers to justice our clients face and how each gift can help address these.

The Home Office has a statutory duty to safeguard and promote the welfare of children, yet parents with dependent children are routinely detained pending removal or deportation. BID's ADAP project provides legal advice and representation to parents facing deportation and potentially permanent separation from their children.

Getting expert reports to support a parent's case can be incredibly expensive. With many reports costing over £1,000, your donation could help our clients overturn a deportation order.

In this article, ADAP Legal Manager Carmen Kearney explains the importance of legal representation in deportation cases threatening to permanently separate families and how expert reports can make or break a case.

What is the ADAP project and why was it set up?

The Article 8 Deportation Advice Project was set up in 2014 to provide legal advice and representation to people challenging deportation based on their family life with a partner or children or their length of residence here in the UK. Many of the people we work with arrive in the UK as minors and then as adults face deportation to a place they have no connection to. In lots of cases they may never have even been there before. Our Advice Line was getting calls from people about bail but the underlying deportation matter wasn’t being dealt with. There is no legal aid available for challenging deportation based on Article 8, the family and private life issues, so there was a clear need for advice to fill that gap and the ADAP project was born.

How often are you contacted by people who came to the UK as children and/or have children of their own who were born here?

I’d say the majority of our cases are those where they have a British partner and children. If they haven’t still got a partner, they have a former partner and children that they’re still in contact with. BID alone have many clients who arrived in the UK as young children which reflects the fact that there are a large number of people out there who came to the UK as minors, grew up here and are now facing deportation.

How did the legal aid cuts worsen the situation for people challenging their deportation on the basis of long residence and/or family life in the UK?

It had a devastating impact, because it meant that people now have to prepare their own cases and represent themselves in the court of law. It’s very hard for people without a legal background to understand what they need to do, how to prepare a case, what’s required of them and then to actually, in court, advocate for themselves. That is hard in any situation, but it’s particularly hard when what you’re facing is potential deportation whereby you could be removed, separated from your family and potentially not be able to come back at all. So there’s a huge emotional issue as well, which makes advocating for yourself even harder. Basically the legal aid cuts have put people at an immense disadvantage. Forced to advocate for themselves, people end up in court facing the Home Office, who have got their bureaucracy, are able to prepare their cases and know the case law. Trying to argue against all that without legal representation results in inequality of arms and it has badly affected peoples’ access to justice.

How essential is it to provide expert reports to support a client’s case?

The most common type we need are independent social worker reports, which would focus on the best interests of the child and what the impact on the child would be if the carer or parent is deported. They’re pretty essential now because we’re finding the courts increasingly require expert evidence of the impact on a child (rather than just a statement from the parents or a letter from the school) about how the child has been affected, for instance, when their parents have been in prison. Such evidence can consider how a child is likely to react if the parents are removed permanently or semi-permanently. We need to make applications for legal aid funding to get those reports quite frequently and they can actually be the key factor to making or breaking a case. They’re expensive and obviously depend on the situation the family is, how many children there are, what are the circumstances of the children. We find the average would be £1,500 for a report. For those people who are not entitled to legal aid funding the lack of such a report can be the very reason why they might not succeed with their case. Psychological reports are the other type we need. When a person has psychological ill health issues, we need an interview by a psychologist or psychiatrist and they can be even more expensive depending on the nature of the condition. We’re looking at a few thousand. You might also need a risk of reoffending report and they are again very expensive. So expert evidence is really important, particularly in non-EEA cases, because there is less protection against deportation, and we need them increasingly.

What is it like for families where a parent is facing deportation?

Obviously it can be devastating. What they’re facing is the family being torn apart, potentially facing a parent being removed and not being seen again in the flesh. There’s remote means of contact but if somebody is being deported to Jamaica or India, it’s going to be extremely expensive for that family to visit. If the parent has been involved in caring for the child, taking the child to school, being there to support everyday family life, then it is just blown apart. I think it’s hard to put into words what these people feel, apart from saying they think their family will fall apart and that they don’t know how to cope.

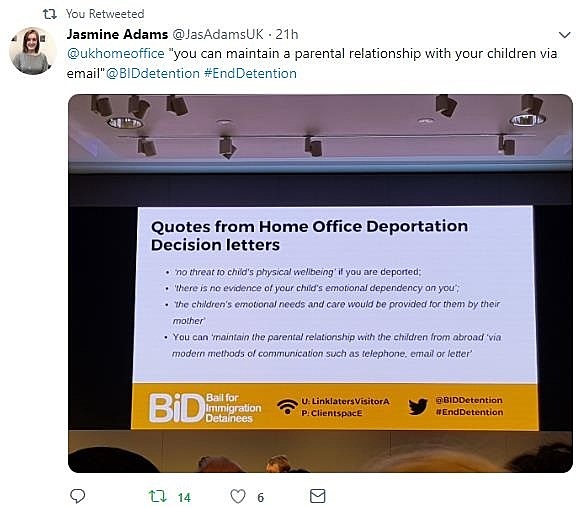

What does the Home Office do to safeguard the wellbeing of children with a parent facing deportation?

The Home Office has a legal duty to promote and safeguard the welfare of the child but the approach we find is a very cursory. They often say there is nothing to show that the child’s welfare will be affected by the parent being removed or that the parent is not financially supporting the child – which may be because they are not allowed to work or get any benefits – or that there’s nothing to show that the child requires the parent’s emotional support.

The starting point surely should be that a parent who is involved in the care of the child and living with the child provides emotional support and that that is essential for the wellbeing, growth and development of the child. But the Home Office start from the point of there’s nothing to show the child will be harmed by you being removed, which is a very odd approach to safeguarding and promoting the welfare of a child.

The Home Office quote their duty in decision letters but they very rarely will carry out proper assessment, even of the evidence they have, of the impact on the child. Even when potential issues are raised about the child missing the parent or not doing well at school since they’ve been away, it’s very rare that the Home Office actually takes steps to find out more about that. They’ll just say there’s no evidence the child’s well-being is being directly affected. Because people facing deportation may not understand the legal process they might not provide the right kinds of evidence but they will raise issues that should be explored, and that is indicative of the Home Office’s very casual approach to their duty to safeguard the best interest and welfare of the child.

How can the Home Office be held to account?

The Home Office is partly held to account by the court in deportation appeals. But of course they’re these are individual cases and it does not generally alter the practice of how they decide to maintain detention or decide to deport. The only way to do that really is through litigation whereby their policies and practices are held up to scrutiny. It is also hard to change the culture of the Home Office. Even if you win in cases due to litigation and get policies changed, you need to have a culture which takes the duty to treat the best interests of the child as a primary consideration seriously, that’s a critical thing.

What advice would you give someone facing deportation?

Number one is that it is best to have a lawyer. If you can’t pay for a lawyer, I think it is worth seeing if you can get legal aid exceptional funding. We have a leaflet on our websitefor making applications for exceptional funding. If that’s not possible, then it’s important to try to prepare the case as much as they can themselves and we havelots of leaflets on our website to guide them to go through that. But the reality is that it is very hard for someone to do it on their own and my main advice would be that they need to have a lawyer, which is why our position is still very much that legal aid should be restored. With something as important as deportation and potential separation from a family, or being removed from a place you have lived from early childhood, people should be able to have proper access to justice and be able to have the opportunity to fight their case fairly in court - and you can’t do that without legal representation.

Getting expert reports to support a client's case can be incredibly expensive.

Help us to build the best possible case for our clients by donating to our Anti-Birthday campaign.

Make an Anti-Birthday donation